Policy warnings can no longer be ignored

Inflation has likely peaked, but the IMF projects that it will not fall into the Reserve Bank’s 2 per cent to 3 per cent target range until 2026, beyond the official timetable of late 2025. Even the Reserve Bank’s gradual forecast return to target would risk unanchoring medium-term inflation expectations as residential rents climb, service sector labour shortages persist, and state governments pump money into new infrastructure.

IMF sees need for more tightening

Productivity has fallen alarmingly in absolute terms, so labour costs per unit of production are rising faster than nominal wage increases. That puts all the burden on monetary policy to curb demand, and pushes out the point at which rates can come down again.

And some of the big handouts made in the pandemic are still sitting in household savings, blunting the impact of the Reserve Bank’s interest rate rises in slowing spending and the economy.

The IMF prescription: don’t let up yet, tighten rates further, and stop adding to spending as federal and state government budgets loosen while inflation is still high. But the IMF says Australian governments also need to spend better. They need to prioritise what will lift productivity and reduce carbon emissions, rather than spending on projects that just add to demand the economy is already struggling to meet.

Underneath everything is Australia’s dismal rate of productivity, which the country shares with many other advanced nations. What is unique to Australia is how the tax system exacerbates the problem. The IMF could not be more explicit in saying that tax reform is “indispensable” to productivity reform.

Australia relies more than its peers on excessive taxing of workers’ incomes. That kills incentive and slows growth. But it is additionally “amplifying” the pressures of Australia’s ageing society as we depend on fewer workers to support more pensioners, says the report. That will happen through the stealth tax of bracket creep.

Tax reform is a priority

Here is the IMF telling us that there is now no way out of reforming the tax system, moving more of the burden onto indirect taxes such as the GST. If there are regressive effects, they can be dealt with through compensation.

The government has made a minor start on reform by cutting superannuation tax breaks for rich retirees. Yet it is relying on a far greater intergenerational unfairness on young workers to deal with the wider population of retirees.

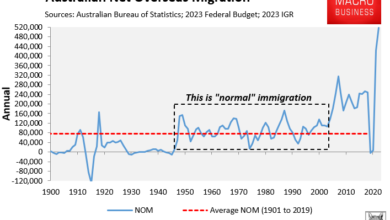

It is not all bad news, of course. People still want to come to Australia. There were 500,000 catch-up arrivals last year as the border reopened, and an astonishing one in three workers is now overseas born. Labor has mostly resisted populist pressure to curb them. The quality of migration is high, with far more tertiary-educated arrivals than the OECD average. They will buffer our productivity numbers in the years after they settle – while, the IMF says, historically not adding to inflation.

Migration does add to pressure on housing and rents. But the shortage of housing is, like so many things in this report, a result of Australia’s own poor policy choices, or perhaps no choices at all – governments happy, as with the tax system, to just let things slide along. Reports like this one are now becoming flashing red lights that can no longer be ignored.