Economic Outlook | Statement on Monetary Policy – August 2023

Global growth is forecast to remain well below its historical average over the next two years, as the

lagged effects of monetary policy tightening continue to weigh on demand. The central forecast for growth

in Australias major trading partners has been revised down, partly because Chinas post-COVID-19 recovery has been weaker than expected (see Chapter 1: The

International Environment).

Growth in economic activity in Australia is forecast to remain subdued over the rest of the year as

cost-of-living pressures and the rise in interest rates continue to weigh on domestic demand

(Table 5.1). It is expected that growth will then increase gradually over the remainder of the

forecast period, supported by an easing in these headwinds and a pick-up in household wealth. Labour

market conditions have been very tight but these are forecast to ease, with an increase in both the

unemployment and underemployment rate over coming years as a result of subdued economic growth. Inflation

is forecast to decline to be around 3¼ per cent by the end of 2024 and to be back within the

2–3 per cent target range in late 2025. Goods prices have

accounted for most of the decline in inflation so far and this is expected to continue in the near term

as the resolution of supply disruptions flows through to prices paid by consumers. By contrast,

electricity costs will increase, and high services inflation is forecast to persist. There are several

key domestic uncertainties that may result in different outcomes than forecast. These are discussed at

the end of this chapter.

| Year-ended | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 2023 |

Dec 2023 |

June 2024 |

Dec 2024 |

June 2025 |

Dec 2025 |

|

| GDP growth | 1½ | 1 | 1¼ | 1¾ | 2 | 2¼ |

| (previous) | (1¾) | (1¼) | (1½) | (1¾) | (2) | (n/a) |

| Unemployment rate(b) | 3.6 | 4 | 4¼ | 4½ | 4½ | 4½ |

| (previous) | (3½) | (4) | (4¼) | (4½) | (4½) | (n/a) |

| CPI inflation | 6.0 | 4¼ | 3½ | 3¼ | 3 | 2¾ |

| (previous) | (6¼) | (4½) | (3½) | (3¼) | (3) | (n/a) |

| Trimmed mean inflation | 5.9 | 4 | 3¼ | 3 | 3 | 2¾ |

| (previous) | (6) | (4) | (3¼) | (3) | (3) | (n/a) |

| Year-average | ||||||

| 2022/23 | 2023 | 2023/24 | 2024 | 2024/25 | 2025 | |

| GDP growth | 3 | 1½ | 1 | 1¼ | 1¾ | 2 |

| (previous) | (3¼) | (1¾) | (1¼) | (1½) | (1¾) | (n/a) |

|

(a) Forecasts finalised 2 August. The forecasts are conditioned on a path for the

Sources: ABS; RBA.

|

||||||

The forecasts are based on some technical assumptions. The path for the cash rate reflects expectations

derived from surveys of professional economists and financial market pricing, with an assumed peak in the

cash rate of around 4¼ per cent by the end of 2023 before declining to 3¼ per cent by

the end of 2025. This compares with an assumed peak in the cash rate of 3¾ per cent in the May

Statement. The exchange rate is assumed to be unchanged at its current level, which is

broadly unchanged relative to its level at the May Statement on a trade-weighted basis.

Petrol prices are assumed to be broadly unchanged around their June quarter average. The level of the

population has been revised higher, reflecting stronger-than-expected growth in recent quarters; over the

next couple of years, year-ended population growth is expected to decline from its recent rate of around

2 per cent back to its pre-pandemic average of around 1.5 per cent.

Inflation in Australia is easing

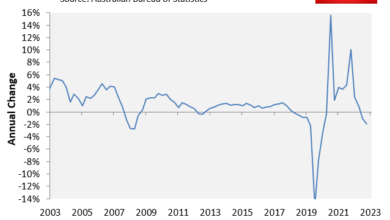

Consumer price inflation in Australia continued to decline in the June quarter but remains high and

broadly based (Graph 5.1). While goods price pressures have continued to ease, services inflation

remains persistently high, as has been the case overseas. The outlook for headline and underlying

inflation remains similar to a few months ago. Recent evidence of stronger growth in the measure of unit

labour costs (partly driven by weaker productivity) and higher rent inflation have largely offset the

effects of the small downgrades to the forecasts for economic activity and weaker-than-expected goods

price inflation in the June quarter. Inflation is forecast to decline to around 3¼ per cent by

the end of 2024, and to be within the target range at 2¾ per cent by the end of 2025.

Graph 5.1

As has been the case for some time, energy prices are forecast to add significantly to inflationary

pressures over the coming year. The average change in household and business electricity prices remains

uncertain; however, the impact of increases in electricity prices on the CPI will be partially offset by

government rebates under the Australian Governments Energy Price Relief Plan and various state

government initiatives. Electricity prices are forecast to add around ¼ percentage point to headline

inflation over the 2023/24 financial year, similar to the forecast

three months ago.

Goods price inflation is forecast to moderate further in the period ahead as the easing in global upstream

costs continues to be passed through to final prices amid slowing growth in demand. This is consistent

with the experience in other advanced economies, albeit lagged. Firms in the Banks liaison program

have reported significant supply chain improvements and easing in some non-labour input cost pressures,

most notably for international freight and some imported goods. Domestic cost pressures – such as

energy, labour costs and logistics – remain a source of upward pressure in firms pricing

decisions, though these are expected to ease later in the forecast period.

Services inflation is forecast to remain high in coming quarters amid rising labour costs and a still-high

level of demand, before easing gradually as demand moderates and generates spare capacity. Rent inflation

is forecast to increase further over the period ahead as rental vacancy rates remain low, and as housing

supply responds with a lag to population growth.

Underlying inflation is forecast to decline over coming years to be around 3 per cent by the end

of 2024 (Graph 5.2). The decline in inflation over the remainder of 2023 is expected to be driven by

the resolution of supply disruptions and slower growth in demand (Graph 5.3). Ongoing tightness in

the labour market and energy price increases are expected to keep domestic price pressures elevated in

the near term before they start to ease later in the forecast period. There remains a high degree of

uncertainty around the speed and extent of the decline in inflation expected in the period ahead. On the

one hand, lower goods price inflation from the resolution of supply chain issues could come through

sooner and swifter than anticipated. On the other hand, domestic price pressures may be stronger and more

persistent than expected. These risks are discussed further in the section on Key domestic

uncertainties below.

Graph 5.2

Graph 5.3

Economic growth is expected to be weak in the period ahead

GDP growth is forecast to remain subdued over the rest of 2023, with GDP per capita declining over this

period (Graph 5.4). The soft near-term outlook reflects subdued growth in household consumption as

higher interest rates and cost-of-living pressures weigh on real disposable income. However, higher

household net wealth – reflecting the recent increase in housing prices – is forecast to

provide some support. Ongoing capacity constraints and weak demand for new housing are forecast to weigh

on dwelling investment until mid-2024.

Graph 5.4

GDP growth is forecast to increase gradually from early next year, supported by household consumption and

public demand. Household consumption growth is forecast to increase to around its pre-pandemic average,

supported by a recovery in real income growth and a pick-up in household wealth. Exports will continue to

be supported by the rebound in tourism and solid growth in education-related travel.

Consumption growth is forecast to remain subdued in the near term

Household consumption growth is forecast to remain subdued over coming quarters (Graph 5.5). This

reflects weak growth in real disposable incomes as the strong growth in labour incomes is being more than

offset by high consumer price inflation, the earlier tightening in monetary policy and higher tax

payable. Consumption growth is forecast to pick up to around its pre-pandemic average by late 2024 and

remain around that rate over 2025. The increase in consumption growth is expected to be supported by a

fading in the current headwinds to real income growth as inflation declines, interest rates are assumed

to be past their peak and growth in household wealth picks up. The Stage 3 tax cuts will also

support income and consumption from mid-2024.

The household saving ratio is forecast to continue to decline over the next year or so, before increasing

gradually from mid-2024.

Graph 5.5

The outlook for private investment has softened but remains positive

Labour shortages are expected to continue weighing on the pace of residential and non-residential

construction throughout the rest of 2023. Shortages of finishing trades – such as internal fitters,

tilers and painters – have been a significant constraint on firms ability to work through the

large existing pipeline of residential construction. Some firms have been experiencing cash flow issues

and insolvencies have risen in the construction sector, which may result in further delays to project

timelines.

Further out, capacity constraints are anticipated to ease, and firms will continue to work through the

existing pipeline of residential and non-residential construction work to be done. Although demand for

new housing has been weak, strong population growth and higher housing prices are expected to support a

recovery in demand and residential construction activity over coming years. While strong inward migration

and high rental yields will support demand for new dwellings, higher density housing supply typically

responds with a significant lag due to long planning and construction lead times. After gaining planning

approvals and pre-sales, the average apartment building takes more than two years to build.

Non-mining machinery and equipment investment is forecast to remain at an elevated level in the near term,

consistent with information from the ABS Capital Expenditure Survey, before easing further out. Mining

investment is forecast to grow over the rest of 2023, before easing slightly as work on expansionary iron

ore and oil and gas projects winds down. The majority of mining investment currently underway remains

sustaining in nature and is intended to replace ageing infrastructure.

Public demand is expected to grow

Public consumption is forecast to increase modestly over the remainder of the year, with lower

pandemic-related spending offset by temporary expenditures on electricity rebates. Further out, the

expansion in public consumption will be supported by public spending programs such as the National

Disability Insurance Scheme and aged care.

The existing pipeline of public infrastructure work is anticipated to support a high level of public

capital expenditures for several years, although the speed of the rollout will continue to be affected by

capacity constraints in the construction sector in the near term.

Education and travel will drive growth in exports

Export volumes are forecast to continue to grow modestly over coming years, driven by services exports.

The number of student visa holders in Australia is around its pre-pandemic level and is expected to

continue growing strongly, consistent with pre-pandemic trends. Overseas tourist arrivals are around

80 per cent of their pre-pandemic levels and are also expected to continue growing strongly as

airline capacity returns. Resource exports are expected to grow slowly, supported by a recovery in coal

exports in the near term and small expansionary iron ore projects further out in the forecast period. By

contrast, rural export volumes are forecast to decline as growing conditions deteriorate following an

exceptional couple of years. Warmer and drier conditions are expected over the latter part of the year

amid an increased likelihood of an El Niño event, which is generally associated with lower-than-average

rainfall across the eastern seaboard of Australia.

The terms of trade are expected to fall in the June quarter, driven by a sharp decline in coal prices

(Graph 5.6). The terms of trade will then continue to decline over the remainder of the forecast

period as commodity prices fall, though this will be partly offset by a gradual easing in import prices

as supply chains improve.

Graph 5.6

The unemployment rate is forecast to increase as economic growth slows

Employment growth is forecast to moderate over the remainder of this year as a result of a period of

subdued economic growth and an associated softening of labour demand (Graph 5.7). In addition, hours

worked have been a key margin of adjustment to labour demand and have grown by more than employment since

the start of the pandemic; average hours worked are forecast to decline from now onwards as part of the

expected labour market downturn. Participation in the labour force is expected to be sustained around

historically high levels over the forecast period. The effect of the cyclical slowing in the labour

market is expected to be partly offset by the continuing of the current trends of higher participation by

female and older workers.

Graph 5.7

Labour market spare capacity remained around multi-decade lows in the June quarter, though a broad range

of measures suggest the labour market is not as tight as it was in late 2022. Labour underutilisation (as

measured by the unemployment rate and by people working fewer hours than they want) is expected to

gradually increase as labour demand moderates while the labour force continues to grow; population growth

supports growth in labour supply while also adding to aggregate demand in the economy. That said, the

unemployment rate is expected to remain below pre-pandemic levels throughout the forecast period

(Graph 5.8).

Graph 5.8

Wages growth is expected to increase further

Timely indicators suggest that wages growth was steady in the June quarter ahead of the implementation of

the Fair Work Commissions (FWC) award and minimum wage changes in July. Firms in the Banks

liaison program report that their current wages growth and year-ahead expectations were steady at around

4 per cent in the June quarter. Market economists and unions expect wages growth to be 3½ to

4 per cent over the year ahead, before moderating over 2024/25.

Year-ended growth in the Wage Price Index (WPI) – which measures changes in base wage rates for a

given quantity and quality of labour – is forecast to be 4 per cent in the second half of

2023, before declining gradually to around 3½ per cent by the end of 2025 (Graph 5.9). The

near-term outlook is slightly stronger than a few months ago. Developments in government wage policies in

several states, the annual minimum and award wage decision by the FWC and the 15 per cent wage

increase for aged care workers will support wages growth over the rest of the year. WPI growth is then

forecast to ease at a gradual pace over 2024 and 2025 as spare capacity in the labour market increases

and inflation declines. Inertia in the wage-setting process and some lagged catch-up in real wages mean

the decline in wages growth is forecast to be slower than the decline in inflation (Graph 5.10).

Graph 5.9

Graph 5.10

Broad measures of labour income are expected to grow at a faster rate than the WPI over the first part of

the forecast period, as employers use bonuses, allowances and other non-base wage payments to retain or

attract staff. These broader measures imply less of a decline in real wages than suggested by the WPI

measure. As labour market conditions ease, the gap between growth in the WPI and broader labour cost

measures is forecast to close.

Recent labour productivity outcomes have remained weak. Together with solid growth in average earnings in

recent quarters, this has seen year-ended growth in unit labour costs reach its highest level since 1990

(excluding pandemic-impacted outcomes in 2021). The forecasts for labour income remain consistent with

the inflation target, provided productivity growth returns to its pre-pandemic trend.

Key domestic uncertainties

The outlook for China is uncertain

Chinas uneven recovery from COVID-19 restrictions has created

uncertainty around the outlook for demand for bulk commodities and, in turn, the prices of

Australias key exports and terms of trade. Demand for residential property in China has weakened

significantly. This could lead to an even more prolonged downturn in real estate investment and lower

steel demand. By contrast, policy measures to stimulate the property sector, if broad in scale and

impact, could increase the prices of bulk commodities in anticipation of stronger steel demand.

Consumer confidence in China remains subdued and heightened economic uncertainty could lead to enduring

incentives for households to prefer saving over discretionary consumption. If consumption growth settles

at a lower trend, this poses additional downside risks to Australias exports to China, including

for education and tourism services as well as consumer goods. Moreover, if Chinas overall growth

settles at a lower rate than expected, this could further weigh on Australias exports through its

effect on the rate of economic growth in Australias major trading partners in the east Asian

region.

The outlook for household consumption is subject to competing forces

The outlook for household consumption remains a key uncertainty for domestic activity. The stronger

outlook for wealth could lead to a larger turnaround in household consumption growth than currently

expected, including via increased housing turnover and increased ability to obtain credit. In addition,

many households built up liquid savings buffers during the pandemic that they can draw upon in the

current environment; spending could be stronger than anticipated if households are willing to spend more

from these savings than expected. This would be reflected in a larger fall in the household savings

ratio. The resilience of the labour market to the slowdown in domestic activity could, if sustained,

contribute to stronger-than-expected outcomes for household incomes and consumption. The realisation of

these stronger outcomes would result in domestic inflationary pressures easing by less than expected.

Weakness in household consumption could persist for longer than expected if weak real disposable income

growth has a larger-than-expected effect, particularly on low-income households that typically have lower

savings buffers. Many households are well placed to absorb higher interest rate costs without significant

adjustments to spending. However, there is a risk that households, especially those with low savings

buffers and high debt relative to incomes, will adjust by more than expected in response to higher

interest rates. Higher interest rates could also encourage households to save more than expected, which

would affect consumption.

Inflation could be more persistent than expected

Underlying inflation is expected to take a couple of years to return to the inflation target range.

However, it is possible that the easing in inflation takes longer than this. Services inflation is

expected to remain elevated over the forecast period – taking signal from the persistence being

experienced overseas – but there is a risk that it remains stubbornly higher than forecast. In a

high inflation environment, it is easier for firms to increase prices; people also tend to pay closer

attention to changes in costs and prices than when inflation is low, and so may come to expect further

large price increases. While margins outside of the mining sector have been broadly stable in recent

years, firms may expand their margins as costs ease if demand remains sufficiently strong. Alternatively,

there could be stronger feedback between wages and prices. Large increases to minimum and award wages and

the lifting or removal of wage caps by state governments could also have greater spillover effects on the

wages of other workers than currently expected, especially if they become a benchmark for wage

negotiations more broadly. In these events, inflation would be persistently higher throughout the

forecast period, which increases the risk that inflation expectations become de-anchored.

Inflation could also be more persistent if productivity growth does not pick up, which would make the

current outlook for nominal wages more inflationary than expected. The forecasts include an expectation

that productivity growth increases to the rate recorded in the years preceding the pandemic. Productivity

growth since the beginning of the pandemic has been weaker than this – in fact, measured

productivity does not appear to have increased at all since 2019 – although the pandemic has made

it difficult to discern underlying trends.

Rent inflation could also be higher and more persistent than expected. Strong population growth is

occurring at a time when the rental market is already very tight and it will take time for supply to

respond. Higher rents are likely to encourage the average number of people living in each dwelling to

increase, which would be a reversal of the decline that occurred during the pandemic as people sought

more space. Conversely, further reductions in household size would put further pressure on the rental

market through higher prices and lower vacancy rates.

Goods prices could decline significantly

The inflation forecasts assume that goods prices stabilise at a high level rather than decline over coming

years. Supply chain conditions are back around pre-pandemic norms and goods inflation has eased in most

advanced economies. Large or widespread declines in goods prices would moderate inflation outcomes by

more than currently expected. One way this could occur is if the simultaneous tightening of monetary

policy across many economies affects demand by more than the sum of individual-economy effects would

imply. To give a sense of the magnitude of this risk, if prices for consumer durables reversed one-third

of the price increases recorded since the onset of the pandemic, year-ended headline inflation would be

around ½ percentage point lower than the current forecast. This would mean that headline inflation

would be around the middle of the inflation target range in 2024, instead of being above it.