Immaculate disinflation is unlikely in Australia

This slight easing in labour conditions may not be enough to bring wages growth back to rates consistent with the RBA’s inflation target. The tight labour market and workers’ claims to be compensated for high inflation saw wages growth pick up to around 4 per cent.

The RBA has been forecasting wages growth to slow to 3.5 per cent, which to be consistent with 2.5 per cent inflation will need productivity growth of 1 per cent. Workers are estimated to be less productive today than they were before COVID-19, so with the disruption passed it’s reasonable to assume that there will be some bounce back, but to what?

Consistently achieving 1 per cent productivity growth seems ambitious without a reform agenda.

Productivity growth can come from technological innovation and a more skilled workforce, or removing inefficiencies in the economy. Across rich economies, productivity growth has declined over recent decades as we’ve used up the quick wins, and before the pandemic was averaging only 0.5 per cent. Consistently achieving 1 per cent productivity growth seems ambitious without a reform agenda.

Given the uncertainties about whether monetary policy is tight enough it’s useful to compare to historical and international benchmarks.

Historical benchmarks summarise how the RBA, and other central banks, have set policy in the past based on how far inflation was from target and some measure of economic spare capacity. Spare capacity can be based on the unemployment rate (relative to the NAIRU, the unemployment rate where inflation is neither increasing or decreasing) or an estimate of the level of GDP relative to the economy’s potential GDP (“output gap”).

There’s a lot of uncertainty in these measures, often referred to as “Taylor rules”. They depend on estimates of spare capacity and the “neutral” interest rate that is neither stimulatory nor contractionary. So it’s useful to use a selection of excess capacity measures and weights for how to bring all the parts together.

Almost all these benchmark rules, including in the RBA’s own model, indicate that given inflation and the lack of spare capacity in the economy the cash rate should be higher than its current level of 4.35 per cent. Many of these rules suggest the cash rate should be around 5 per cent.

Less restrictive

An alternative benchmark is to compare how restrictive monetary policy here is to other advanced economies, where high inflation starting with tight labour markets are common features. The basic metric for monetary policy’s stance is the central bank rate less the inflation rate.

This comparison highlights that monetary policy in Australia is less restrictive than in most other advanced economies, in absolute terms and relative to the historical average and range.

A less restrictive policy stance in Australia is not justified by economic conditions. Australia does not rank well in terms of how far inflation is above target and the tightness of the labour market. The US, euro area and Canada have all tightened much more given their macroeconomic conditions and so have better prospects of containing inflation.

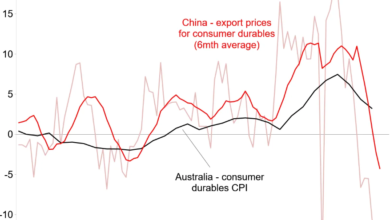

There are many different paths that inflation can take in returning to target and maybe we are witnessing an immaculate disinflation. But given the evidence that the cash rate has not been high enough, there is an increased risk that inflation will be persistent and so it will take longer before the RBA can cut the cash rate.

Have your say

We are always interested to hear your views on current topics.

Guidelines for how to write an opinion article are here.