How low unemployment is delaying interest rate cuts

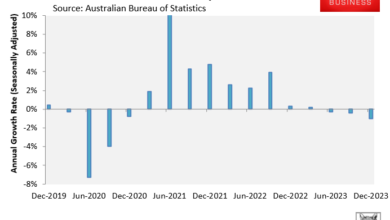

The Albanese government can only publicly welcome the strength of the jobs market, of course. Nor is Bullock likely to repeat her accurate but politically sensitive assessment in a speech last June that unemployment would have to rise to about 4.5 per cent to help bring inflation down to the RBA target of 2-3 per cent. Last month’s monetary statement declaring no change in the cash rate merely noted that the unemployment rate was expected to increase further.

But a receding horizon for rate cuts is always difficult for political leaders eyeing their election prospects. There’s still time for the RBA to assist with rate cuts given the Labor government can afford to wait another year. The dilemma is particularly acute for US President Joe Biden who had been counting on a few rate cuts before November.

A buoyant US economy – along with inflation that seemed to be coming back under control – had encouraged the market to believe a feather-soft landing was pretty well guaranteed. But what was happily termed “immaculate disinflation” is not following the tidy path anticipated for 2024.

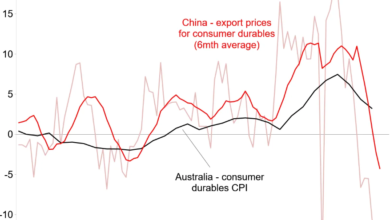

Manufacturing pressures

Despite the price of most goods falling, the price of services is continuing to jump – in some cases very sharply. In the US, core inflation has been rising again over the last three months. Like Australia, one of the key factors in this is the spiralling price of rentals.

Australia’s inflation numbers for the March quarter to be released next week are certain to reinforce this vicious circle. No doubt Greens senators will push for another Senate inquiry to allow them to conduct more inane grilling of chief executives. But Labor is unlikely to encourage the same convenient political diversion on cost of living blame-shifting that was indulged by the Greens-led inquiry into supermarkets this week. The febrile mix of housing shortages becoming worse at a time of massive immigration is much harder political theatre for the government to manage.

The main game in Canberra in coming weeks will be how the combination of low unemployment with too high inflation influences Chalmers’ budget presentation on May 14. The treasurer is trying to steer a course between responding to community anger about the cost of living without introducing a raft of new spending that will add to those inflationary forces.

That’s already problematic given the huge increases in government spending on programs like the National Disability Insurance Scheme, healthcare, aged care and childcare, with no sign of easing. Political reality means there will still be some additional relief for households, although limited, with Labor also promoting its version of the stage three tax cuts to start from July 1.

But the government’s big policy sell will be promising to boost the economy – and jobs, jobs, jobs – by offering subsidies, cheap loans and possibly tax breaks to encourage investment in manufacturing and clean energy projects.

It maintains a “Future Made in Australia” is economically virtuous policy that is made for a new era when all countries are now adopting their own version of such assistance. That’s despite the strong concerns of economists that this Labor government may be about to repeat the errors of Australia’s past in diverting resources to what are ultimately unviable industries.

Naturally the government rejects this criticism, with Anthony Albanese insisting that this is not about “old protectionism [or] corporate welfare”, with any loans to be repaid.

But the apparent imminent closure of a key plastics maker and chemical major Qenos demonstrates the extreme costs and commercial pressures undermining existing Australian manufacturing, compounded by the increase in the price of gas.

Chalmers is fortunate in having fiscal room to manoeuvre given the surplus is still so cushioned by rising income taxes and strong commodity prices – once again expediently above last year’s typically cautious budget forecasts.

While RBA economists are predicting the iron ore market may be near its peak, for example, the big miners are sounding extremely confident about the immediate outlook for Chinese demand. That sort of industry analysis has been far more reliable than Treasury’s or the RBA’s over the past decade.

The miscalculation is at least useful for the treasurer to have in his back pocket. But negotiating the economic shoals of 2024 will require much more difficult judgments.